I wonder what I look like. Each day I sit in a 6 X 6 cubicle at work. I sit near the end of the floor so people walk up from behind me, see the back of my head, read my name plate, and turn to say hi if they know me. Work. The office. Part of my daily routine, a much-needed structure in my life. I drift without structure, a lone survivor on a life-raft, no land, no people, no measure of myself, nowhere to plant my feet. The 6 X 6 beige panels keep me grounded and sane. I’m a Taurus (look it up), which makes me the perfect person to work in a cubicle-ed environment.

Today is my 17th anniversary at my company. Seventeen years is a long time to work in one company. I have a long history of cubicle-dwelling.

My head pivots back and forth between my two 21-inch monitors, as my fingers click-clack on the keyboard. I bring up a gigantic Excel spreadsheet on the left monitor, and the company’s intranet Web page on the right. As the years go by, we increasingly employ shared Web space for dialogue, data, files, and other equally scintillating work objects. If I stop typing for a moment, I can hear several of my co-workers also click-clacking on their keyboards, in their 6 X 6s, some drumming quickly and some tapping slowly, perhaps composing a difficult email to the senior management.

My thoughts turn to my mother whom I lost in February to cancer. What would she think if she saw me sitting in my cube like an air-traffic controller with the two big screens in front of my face? What would she think about the complicated-looking spreadsheet to my left, or about the never-ending online activity to my right? I work in a world that would make little sense to her.

I did try to teach her how to use a computer. She was bored with Wheel of Fortune and the usual crap that was on TV. I was a terrible teacher. My mother frustrated me. Her hands were nervous and twitchy on the keyboard, and she kept trying to guess what I was going to say next rather than listening. I wasn’t very nice. I wrote down what I could so she could learn on her own when I wasn’t home, but it didn’t work out. Once day she called me at work to tell me the mouse was broken. I told her she needed to hold it in her right hand move the cursor across the screen.

“I am,” she cried, “but nothing is happening!” She was truly stressed. She was in her late 70s and this was a different world to her.

“You’re trying to move the cursor across the screen?”

“I’m moving the mouse across the screen, but nothing is happening.”

After another five minutes of this conversation, I burst out laughing.

“You are literally picking up the mouse and sliding it across the monitor, aren’t you?”

And yes, she was.

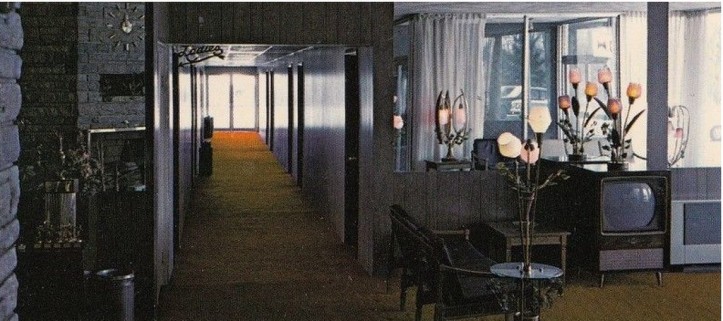

My mother, born in 1930, worked for much of her adult life. Her last and longest held position was as a bookkeeper for the now defunct Route 138 Motel in Easton, Massachusetts. The motel went out of business in the late 1990s, and now there is a Roche Brothers Supermarket Plaza, a CVS drug store, and medical buildings on the property that once held a grimy old two-story motel. My mother had a filthy office; the motel owner was a filthy man who smoked cigars until the walls of his motel turned yellow and brown, and who heaped junk into my mother’s office since she only needed so much space. But she had real walls. And a big metal office desk.

My mother was the bookkeeper at the motel for 30 years. She got the job when I was four and she was 36, just after she and my father separated. When I was older, she told me she applied for the job one night while sitting at the bar in the motel, drinking martinis. The owner came up to her for a chat. No resume was provided. She told him about working on the Fish Pier in Boston for Swanson frozen dinners, about doing the books for Tabby Cat Food. Her hiring at the motel was spontaneous and informal. The year was circa 1966.

When I was a young kid, my mother would take me to work with her during the day, or when I was in school, on days I was out sick. She would wrap me in blankets, and I’d rest my head against the big Great Dane, Max, who lay on the floor between her desk and the owner’s junk. As I got older I paid more attention, and I watched my mother be a bookkeeper. I was mesmerized by her ability to use a 10-key adding machine, with a roll of white paper to keep track of the numbers, the only piece of “tech” on her desk. Her fingers flew across those 10 keys at lightening pace. She didn’t look at the adding machine until she hit the subtotal button, at which point she would enter the number into a paper book of accounts, a “daily” ledger. She had all kinds of paper ledgers and journals to keep, to maintain the motel’s books. I asked her, “Mom, how can you use that adding machine without looking at it?” She said, “I’ve used it so much that it’s a part of me. I don’t need to think about it.”

In 2016, as I sit at my desk, I know what she means. I type so much, and have for all my adult life, that I type fast and accurately, if I just let my fingers do it and don’t think about the letters on the keyboard. If I think about typing, I will make mistakes.

My mother took great pride in her abilities as a bookkeeper, and she was a good one. My father used to say she was a great bookkeeper. He owned his own children’s clothing business in Boston during the 1950s and 1960s, and my mother must have helped him with the books. My father mainly criticized my mother, so for him to be so complimentary about her bookkeeping abilities made me truly believe she was a shining star in her field. I do know she loved to work. She was a role model to me in that way, a mother who worked each day and on her own, after she and my father separated.

Gone are the days of adding machines, big metal office desks, smoke-filled offices and paper ledgers. Gone is my mother. But here I am, using an updated version of her tools: two big monitors and an Excel spreadsheet, and the newest version of an office – the cubicle. I’ve been with this company for 17 years, just 13 more before I have achieved what my mother achieved. If I can ever achieve it.

powerful poignant writing. your mom would be proud.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Suzanne. 😄

LikeLike

Very poignant. Be it comedic or reflective, your voice is strong and always moves.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Margaret. I appreciate that!

LikeLike

Cindy, I don’t know you, but in a kindred way, I read your words. Month after month, I experience what you are describing, not just by what you write, but by my own experiences. Sometimes uncanny. Sometimes I go a month or two without reading your posts, then I find myself eagerly catching up. I’ve lost my best friend, my Mother, I attempt to help the elderly with technology, I remember to respect them and their skills and abilities. I am single. I live with my cat. And your words remind me that I help make up this world. What little affect an individual can have, I have it. Thank you.

LikeLike

Thank you for reading. It means a lot to me. It motivates me to keep writing. It’s so hard losing your mom. You sound like a wonderful person to help the elderly as you do. Please stay in touch.

LikeLike